he change has to come from socialization. It’s the way that people are being taught to interact with other people. I don’t think it’s something that’s going to come quickly; I think it’s a generational issue. If we do enough right things now and teach these younger generations of people what’s up, get them on board early, then a generation or two from now, something can happen.

Diana Arce is an artist, researcher, and activist living in Berlin, Germany. She founded Politaoke, a karaoke-style participatory performance in which audience members are invited to step into the shoes of politicians from their region by delivering portions of political speeches. Arce also founded Artists Without a Cause, an organization that assists in the collaboration between activists and artists, as well as White Guilt Clean Up, a “service provider” that helps white people face their prejudices and become better allies to people of color. A prolific creative activist, Arce continues to create innovative work across a wide range of mediums.

Sarah J Halford: Tell me a little bit about yourself. What’s your practice, and when did you come to Berlin?

Diana Arce: I’ve been living in Berlin for 12 years. I’m from an immigrant family who came from the Dominican Republic. I started as a filmmaker with experimental films, and I moved slowly into performance art and installation.

Toward the beginning, I was dealing with a lot of things about culture, and I was trying to see if I could make other people feel the way that underrepresented groups of people would feel in a situation, to see if I could flip minorities to majorities and majorities to minorities. So, all the work that I was making were experiments of that. Making pieces where if you didn’t speak Spanish, or weren’t from Latin America, you couldn’t understand 80% of what was happening. Or, forcing people to immigrate into an art installation, but the more American you were, the harder it was to get in.

One of my favorite things that happened with that was that a friend of mine who’s from Kenya came, and she got VIP’d through the whole installation. And she was really excited because she was like, “This never happens! Ever!” So, I spent a lot of time doing that kind of stuff, and that was also when I had my first experience coming to Berlin – I came here for a year on a student exchange. Half of my Master’s thesis was about Berlin as well, but it was also about a misconception in Germany, and by most Germans, that they are all white. There’s been a history of black people here since Medieval times, even black people in the courts – like, kings. But there’s this weird thing that World War II did a great job of, which was erasing any concept of any sort of multiculturalism within this culture, and that’s never been fixed. Everything that’s not white in Germany is still considered an “other.”

And so, I came to the way that I make art from this area. With time, the kind of work that I was making moved more and more into public space. It was kind of a slow process – first it was filmmaking, then it was performance on film, and then it was performance in a gallery, and then performance in a window, and then I took to the streets.

SJH: Can you say more about what your practice is now?

DA: It’s largely conceptual, and it’s very research heavy. I spend a lot of time reading. I’m basically interested in bringing other things into focus; bringing things into focus that people don’t normally notice but are the things that they should be focusing on. The medium doesn’t really matter. So, I do a lot of work in public space and on the internet, I am still making films, and I’m trying to make a video game right now, which is kind of weird because it’s totally new for me. But it’s very much about looking at the structures of different aspects of life and then reframing them.

I’ve been doing this project “Politaoke,” since 2007. For me, it’s about finding a way to talk about politics without actually talking about politics, because what happens whenever you talk about politics in a mixed room of people, all they do is get caught up in language and stereotypes of what they believe that the people they believe in tend to be, and then they don’t actually have a real conversation. So, how do you remove the candidate from what they’re actually saying? And the idea for that was like, okay, I’ll put everyone in the shoes of a candidate. If you get to be the candidate, it gets a lot harder to swallow the words if you don’t believe them. And then, people can actually have discussions about what it is that they want from our government and our politicians without thinking directly about the politician.

SJH: How would a night of Politaoke work?

DA: It’s just like a karaoke bar. It’s moderated, either by me or if I’m in another country then I find a local person to do the moderation. It’s non-partisan. I usually try to get a group of people to help me work on it, so there’s usually a team of researchers, and we collect as many speeches as we can find from all the politicians that are running for a particular office or who are from a particular region. We take a certain topic and we try to find all the speeches that we can find from all the candidates on that topic. The key thing is that we try not to find excerpts of a speech, but to find a full speech. Then, we take those full speeches, turn them into transcripts, and those are then taken and turned into karaoke videos. So, the videos themselves are one-to-one in the exact rhythm of the original delivery of the speeches. If they cough in the middle of the speech, it’s on the karaoke video, or if they mispronounce a word or sideline into something else.

What the show ends up looking like is a festive karaoke bar, but instead of just a microphone on the stage, there’s a podium. The audience can see the words as they’re being delivered; they’re right behind the person speaking, really big, and they have a teleprompter and can deliver the speech in any way that they choose, from any politician that’s in the program. So, we don’t choose for the people who participate; the audience chooses for themselves. In exchange for their participation, in the idea of using the same things that political parties use, they “become a member” of the “Politaoke party,” and we give out little gifts to people, like they get a button if they participate. The best speech is chosen, semi-democratically, from the audience, and they get a shirt and are ruled as the “Official Politaoke Party President” of that town. Shows can go between an hour and a half and — I had one show that went like four hours because the audience didn’t want to stop, which was really great. It looks just like karaoke, except there’s no…well, sometimes there is bad singing.

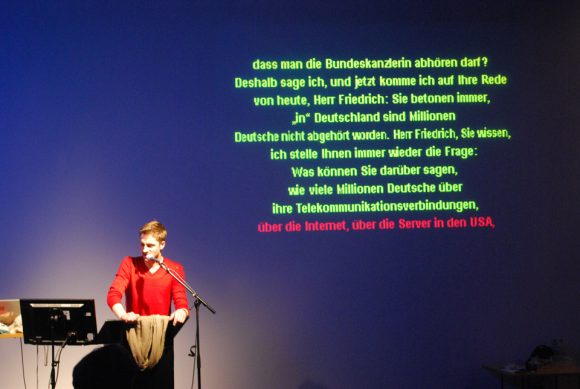

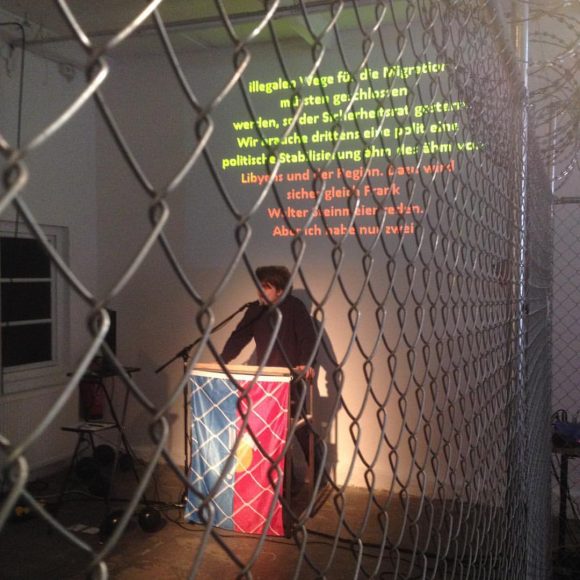

Pictured: A participant performing a speech at a Politaoke event

Pictured: A participant performing a speech at a Politaoke event

SJH: Politaoke is one part of your work, but you also have a few others.

DA: Yeah, one of the latest projects that I’m working on is a project called “White Guilt Clean Up.” It is a service provider to help assist people who are suffering from issues of having white guilt to learn how to be better allies and accomplices to people of color. It started out as a Facebook page and a Twitter handle, and basically it was a free advice column for people who were “suffering” from or having issues with white guilt. Every week would have posted lists of “Dos and Dont’s” like: Don’t wear Indian headdresses to Coachella – this is what that’s wrong. And, if you want to show solidarity with #blacklivesmatter, tweeting #alllivesmatter doesn’t work.

I started bringing in other people, so now we have a “Resident White Accomplice,” who actually writes letters to white people to try to help them better understand why they have privilege. There’s several other people in the collective. But one of the funniest things that came out of it was that someone figured out that we’re here, and they started calling us in to respond to racist events or events that were culturally appropriating people of color. And so, we started to respond to things. It’s always about trying to look at it from a positive point of change. I have no interest in grilling people or telling people, “You’re wrong and eff you!”

One thing that came out of it was – there’s a magazine here that invited a Dutch girl who did black face to come braid people’s hair – but not just to braid people’s hair, but to give white women cornrows.

SJH: Ooof.

DA: So many levels of wrong.

SJH: So many!

DA: And so, they invited this woman, and of course the POC community in Berlin lost it, and someone wrote to White Guilt Clean Up and was like, “White Guilt Clean Up! We need your broom!” And I came in, responded with some things, and I posted a video about what cultural appropriation actually is. It went back and forth and eventually that event ended up getting cancelled, and the magazine asked me to come in and talk to their staff, and now we’re actually organizing a panel with the magazine on cultural appropriation that will hopefully take place sometime this fall. It’s mostly going to be a panel full of POCs.

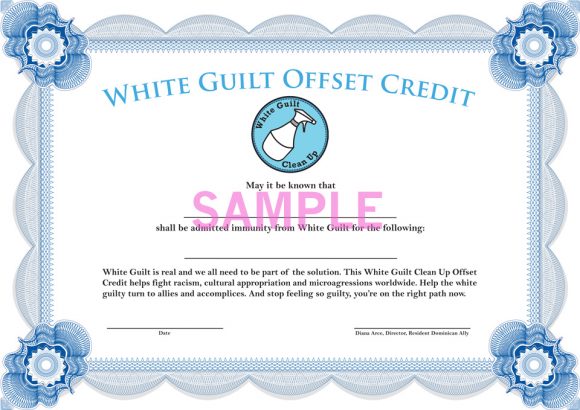

Part of White Guilt Clean Up’s position is that anytime we get brought in for anything, we have to get paid, but a percentage of our money goes to a local organization that’s doing work with POCs, hopefully within the topic of whatever the issue ended up being. So, we’re going to give 10% of the funds that we get to the several black organizations in Berlin. Another part of it is a “White Guilt Off-Set credit” that you can purchase. So, if someone has felt guilty about something racist that they’ve done, or said, or appropriated, you can meet with one of the White Guilt Clean Up consultants and we will talk with you about it and we will quote you a price, and for that price you will get an actual bond that will “absolve you” of your guilt for that particular issue. And then, it’s the same thing with that as well – a portion of the proceeds from whatever we collect in the bonds goes to a local organization to help fund anti-racism work.

The funniest thing about the response, though, is that everyone is really surprised to find out that I’m not white. There have been several events that I’ve gotten to go to recently and someone was like, “Oh my god! You’re White Guilt Clean Up! You’re not white?!” (laughs). But there’s been a really great response from people of color and also a lot of white people who have written us and , “I don’t really understand why this is wrong.” And instead of bashing them or making them feel stupid, we’re like, “Okay, you don’t understand why this is wrong, this is why. Here’s some resources, here’s some things you can read and people you can talk to.” It’s been really great, I’ve been really surprised.

Pictured: A sample “White Guilt Offset Credit” bond to be purchased/earned by those who commission White Guilt Clean Up

SJH: Do you hope that your work will help to create change in larger, systemic issues?

DA: I would like to say that everything I’m making is an attempt to change people’s minds about things and see if you can get to someone effective enough who can actually enact those bigger parts of the change, but that’s mostly never the case. So, I don’t ever really think about the work that I make in the sense of trying to change the system as a whole, but it’s about: How can you change the ideas of actual, individual people? You have the people who agree with you, and what ends up happening with most people who work in art or political art or NGOs is that we all talk to those people all the time. And it’s useless to talk to those people because we already know that they agree with us.

SJH: That echo-chamber effect.

DA: It’s an echo-chamber, it’s preaching to the choir. And then you have the other end of the spectrum where it’s people who completely disagree with you, and there’s also no real point to talk to those people either because it kind of doesn’t make a difference what you say, those people are just so eager to disagree with you that there’s no room for change. But between those two groups of people are the people who are either undecided or don’t know, and that is actually the majority of most people. We don’t really look at things that way because it tends to be that the people on the other ends are the loudest. The people in the middle are quiet, or they don’t say much, or they don’t know that they should say something. And so, I have a keen interest to flip as many of those people as possible to think about things in a different light. And it’s not about necessarily completely agreeing with me on everything, but it’s to have a better understanding of how things are structured.

SJH: Do you have an example of how you’ve been able to reach those people in the middle?

DA: The first time I toured Politaoke in 2008, there was a funny situation where I actually got protested. It wasn’t a big protest, but I was really excited about it! It was like three or four people, and they were really loud and really angry. It was before the show and they were yelling at me about how I’m some pro-Obama outfit or something, and it was great because I got to say to them, “No, I’m not. This isn’t about my personal politics, this is about politics in general. If you look in my program, you can see that I have eight different candidates who are running for president. I don’t just have Democrats or Republicans, I have Libertarians, Constitution party members, the Peace and Liberation party, parties you don’t even know about. You can pick any of these people.” And so, after a bit of canoodling and getting them to calm down a bit, they decided to stay.

One of the guys who was protesting me decided to give a speech. He picked a speech from his favorite candidate, Chuck Baldwin from the Constitution party. It was about immigration. The guy gets up and starts delivering this speech, and he knew everything about the Constitution party – or so he thought. Apparently, he didn’t know about their immigration policy. Their immigration policy is very much á la Trump, but this was back in 2008 so it was even stranger. It’s this guy talking about building a wall between us and Mexico and how he’s just going to send everyone back and take all the Mexican immigrants and put them back over there.

SJH: Scary foreshadowing.

DA: Yeah! And this guy, who loves Chuck Baldwin and loves the Constitution party, happens to have a Mexican wife!

SJH: Wow. Was she there?

DA: No, she wasn’t there, but he happened to, apparently, have a Mexican wife. And so, he kind of loses it in the middle of the speech, he can’t really even finish delivering it. And at the end of the show, he’s sitting there with his friends, and there’s another guy who came to the show who was a Green party candidate running for a representative spot and there was another guy who said he was a Democrat, and they’re drinking a beer with this guy, helping him work through the feelings about the fact that his favorite candidate happens to hate his wife. And it’s clear that his world just opened up, and he had this huge realization that he didn’t really know as much as he thought he did and that there’s a lot more happening outside of these 30-second clips that he’s seeing on the news. It was really amazing to see that.

One of my other favorite things that happened was that we did one show where people were choosing speeches for other people. Everyone thought that John McCain’s NAACP speech was a speech from Obama. It caused a lot of confusion. It was funny because the speech was extremely charismatic and great, but not when it’s delivered by John McCain – he’s horrible at delivering speeches. But you give it a different context and all of a sudden it sounds like it’s something completely different.

SJH: Did it say on the projection screen at the end that it was a McCain speech?

DA: It says in the beginning, usually, but this particular show the audience wanted to do sort of a kamikaze karaoke where they were able to pick speeches for other people. I was able to shut off the screen that shows the person whose speech it is, what speech it is, what part of the speech it is – because no one does a full speech. No one wants to sit and do karaoke for 40 minutes, so we break the speech up into sections, usually by topic, if we can. That particular show was this random show where people wanted to guess who was doing . But it was really funny about how many times they got it wrong. They couldn’t tell whether it was a Republican or a Democrat; the only time they could figure it out were with Libertarians, because they’re like, “You can smoke weed AND you can have guns.” Yup, okay, it’s a Libertarian. Everything else, no one really had a clue about who was who.

And another thing that happened – which, I don’t know how much it affected the people in the audience, but I know how much it affected the person giving the speech – I was in Israel, and I did it with Israeli and Palestinian speeches. When I got in, I was told that I could be shut down at any moment because it could go terribly wrong, which I understood. On the last show, it was in this public square. I was really unhappy that it was there, because anytime you do anything in public in Israel, it has to be covered by police presence. There was a kid who was hanging out and decided to come in and do a speech. He turned out to be a Palestinian teenager, and he gives the speech, and after he’s done he asked to speak to me with the help of someone who could translate. This 15 year old Palestinian boy tells me that that was the first time in his life that he feels like anyone ever listened to him. It was the first time in his life that he actually felt like he had a voice. For me, that was one of the most powerful things that has happened. Who knows what will happen to this kid; a lot of bad things could happen because he’s Palestinian, or maybe he’ll decide to become a politician or, I don’t know, maybe something will grow out of this because he felt like he had a voice, for once. And that’s a pretty cool feeling. Is it going to change the world? Probably not. But you don’t ever know.

Pictured: Diana Arce (at podium) presenting for Artists Without a Cause in 2015. At this event in Berlin, Arce and her collaborators handed out European Crosses of Merit to citizens who helped refugees cross borders.

SJH: Do you hope that your work sparks a fire in people?

DA: I would like to make a spark in people, at least in a few people. That’s sort of the goal.

SJH: And then you let them build the fire as they will?

DA: Exactly. For me, it’s more important – you can go to a protest and stand anywhere, do as much as you want, telling people what they should think, but telling people what they should think never really works. If someone gets ignited by something that you’re doing, by learning from something that you’re doing, that’s the best you can hope for.

SJH: If you had to categorize yourself, and your work by extension, would you call yourself a creative activist?

DA: I would say that I’m a creative activist. Yeah. I would definitely agree with that term. I think it’s better than political artist; I feel like it’s a more encompassing term of what I’m trying to do. Political artist can mean so many things, and there’s so many people who make political art that I think are doing a disservice to culture and are actually destroying things, using people. You can call whomever you want a political artist, but you can’t call someone a creative activist if they’re actively harming people in the process of creating their work. You’ve got Syrian refugees dying in the Mediterranean ocean, and you’ve got artists cracking jokes about having them eaten by tigers.

SJH: Was this an action by the Center for Political Beauty*?

DA: I’m so angry about that. “Activist artists” like this are so useless. They’re doing their whole spiel about this, thinking it’s so funny, but you’re going to ask a refugee to volunteer to be eaten by tigers? No one gives a fuck about a refugee dying. There’s thousands of them dying in the Mediterranean all the time – we’re looking at pictures of babies on the coast of Greece and it does nothing. Who cares about a refugee getting eaten by a tiger – you know what’s more interesting? You know who’s more interesting to watch get eaten by a tiger? A white, privileged European. That they would put their ass on the line and say, “You know what? If refugees don’t get let in the country, tigers can eat me.” They’re not willing to feed themselves to the tigers, but they’re totally happy to exploit poor brown people for their personal gain.

They don’t care about politics; they don’t care about people. All they care about is making themselves bigger. For me, it’s such a disgusting thing to see because there are so many people who are suffering, and there are so many people who are trying to find ways to do better things, and there’s so many people who want to help, but they’re being misdirected and misguided by a group. They’re investing all of their money into a group of artists who are doing nothing with it. Who are basically making themselves richer at the expense of poor people, by producing highly crafted bullshit. Great, good job, you sent a lot of people to go cut a fence, and you made such a hoopla about it, that some of the activists that you took with you got arrested and then you left them there. You’re literally harming the movement for your own personal gain.

And then, a bunch of white folks get to feel good about themselves because they gave 20 euros to your campaign, and it’s 20 euros that they just paid to another group of white folks who are doing nothing. They’re doing nothing. They’re getting richer, making a name for themselves, getting printed in all of the newspapers and magazines, but in the end, when it comes down to actually helping disadvantaged people – zero. I find it disgusting. This last thing for me was like the final straw. I don’t think those guys even get it, but then there’s not even a single person of color in that group, so they wouldn’t get it.

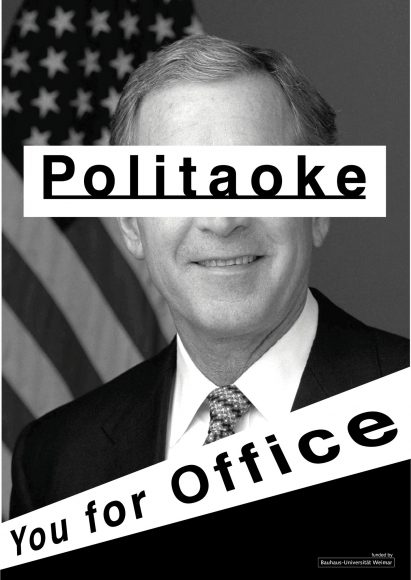

Pictured: Election poster from Politaoke’s 2008 USA Election Tour

(Also pictured: portions of George W. Bush’s face)

SJH: Can you tell me a little bit about Artists Without a Cause?

DA: So, Artists Without a Cause started as an idea from when I got invited to a camp by the Tactical Technology Collective, which does a lot of work on digital security for different kinds of activists all over the world. The camp was 125 or so activists from all over the world, doing all different kinds of stuff. Toward the end of the camp, there was a point where anyone could hold a session for any kind of topic, and I asked if anyone was interested in talking about how to better collaborate – people who define themselves as activists, how they could better collaborate with artists. I was feeling for a very long time that I was making these works, but there was nothing to push it to the next level. What is the way that we can collaborate to help artists to produce materials or to utilize materials produced by artists in order to be better activists, and to share this information?

What the roundtable ended up being was a circle of people asking for advice. There were people working on different projects and they asked about working with certain artists that they haven’t been able to reach, and the artists in the circle gave some tips on what they should try. So based off of that session, started out as researching different things and trying to find people that we would be interested in working with, putting together an idea of best and worst practices, how to work with artists or how artists should be working.

Out of the blue, I got invited by Open Knowledge Foundation to curate a larger group of artists to come to Open Knowledge Festival, which is all these open data scientists talking about how they do their activist work. Our idea was: open data is great and useful, but how do you get people to the information? And artists are a great way to get people to that information. It was funny because at the beginning of the conference, several people came to our table and said, “I don’t really see the point of this – I think it’s a big waste of time,” and we were able to convince a few to go to our seminars and they found that it was interesting and useful for their organizations. I think that when these groups and NGOs work with artists it tends to be an exploitative relationship. The artists end up not having so much creative input.

SJH: So, Artists Without a Cause tries to find ways to make the collaboration more of a partnership?

DA: Yeah, to make it a partnership. Any time that an idea is so new, even if it’s not a large risk, organizations tend to get spooked. NGOs and nonprofits are probably the least experimental organizations that exist; they don’t really have that much interest in changing their structures or trying something new. And then, there’s also the issue of measuring: how do you measure the success of an art project?

SJH: Which is necessary for grant applications, and such.

DA: Yeah, you have to be able to say how many people were affected, what was the outreach, and this and that. We’re trying to come up with ideas on how to frame that, in a way that would work, for these organizations.

SJH: What are your thoughts on that, so far?

DA: I don’t know – it’s really confusing because different kinds of organizations want different measurements, there’s surveying, there’s one-on-one interviews, but I think that the only way that you’re going to get more useful information in these scenarios is to do a qualitative analysis instead of a quantitative analysis. But those are very people-heavy, and it can’t come from the artist’s side. They don’t have the capacity or the manpower to do it. And so, not only are we asking these organizations to take a big risk by bringing in these artists and to give them a bit of autonomy as to how they work with them, but then to also give manpower in order to have the proper analysis to judge whether or not a project was successful. A survey is not really going to cut it.

SJH: Have you ever done any of that analysis yourself, for your own projects?

DA: I mean, I try, but it’s an issue of time. I can send out a newsletter and ask people to participate in a survey, and now I try to interview someone at the end of the shows that I do to talk about how they feel about the show. But that’s so immediate. It’s one thing to be able to interview a person right after the show, but what I think would be more interesting would be to see what they say two weeks after the show. But, do I invest energy in researching the effectiveness of the shows or do I continue doing shows? And I always happen to choose to continue to do shows or work on new projects.

SJH: When you’re at the shows, are there sort of instantaneous metrics that you use to gauge if it’s going well or not?

DA: Oh yeah, for sure.

SJH: Can you think about a time when you felt like the work was really successful?

DA: For me, it’s the more participatory work, which is not about the speed of the participation but it’s about the speed of the want of the participation. So, it’s the number of people you have in the pipeline who want to do something. With Politaoke, that’s very easy, because it’s how many slips you have and how much time are you taking for people to do the show, as opposed to people doing it.

I did a show last year that was amazing; it wasn’t the most people I’ve ever had at a show and it definitely wasn’t the best room I’ve ever had, but it was a show that I moderated the least in. I had no time to moderate because there wasn’t enough time – so many people wanted to do it, and how that happened was so immediate. The first two or three people went up and after that I had a big stack of slips that just kept getting added to, so I didn’t have time to moderate. The moderation is a nice part, because then you can talk about the politics, but people were super motivated and they just wanted to hear it, so I had to get out of the way. That was a great example of something going really well, but on the other had, I had a show that was like five people and they went for three hours. They just kept going. So, it’s kind of different because I don’t think you can measure solely by how many people are there. You can say how many people are there, how many did it, how many times people did it, you can map out which speeches people did. You can talk to people about their personal politics and see if they went further away from what their own politics are –

SJH: What do people typically do?

DA: I think that people tend to start out with the things that they know. Then, you have a few adventurers who want to try something that they have no interest in. Then, you have the people who want to make fun of the politicians that they don’t like, and then you have the people who just want to do one, it doesn’t really matter which one. It’s always those groups of people.

SJH: So, do you give people backgrounds on the politicians before they go up?

DA: If people ask for the information, then it’s provided, and I try to make it so that there’s a bit of stats about the politicians in the karaoke books, and then there’s usually a small excerpt from the speech.

Pictured: A participant performs a speech at the Meine Rede Politaoke event in 2015.

Pictured: A participant performs a speech at the Meine Rede Politaoke event in 2015.

SJH: What about a night when it totally fell flat, just didn’t go well at all?

DA: Well, I thought the show with five people was going to suck, but it turned out to be really amazing. To this day, I don’t think I’ve had a bad show. I only had one show that I considered bad, but it was because I got double-booked with a band and we couldn’t start right away because the band unhooked all of my equipment. But that’s the only show that I would consider as bad.

SJH: You said that when it’s going really well, you don’t have to do so much moderating. Do you feel like it’s a bad sign when you have to do more?

DA: I don’t think the moderation is a signifier in it being “bad” or “good,” it’s just different audiences or different ways. So, I made the misconception that I thought that I would have to do a lot more moderation for a German audience, because German audiences are not really interested in participating or putting themselves in the spotlight, supposedly. I had all of these conceptions of how it was going to be to do in Germany, and they were all wrong. It took three speeches. It was the fastest show I ever had, with the least moderation that I ever had. And then, I’ve had other shows where I spent so much time talking to people and encouraging people, trying to get them to participate, but all of that time was still very well spent talking about the politics and about what the different aspects of things were, giving bios of certain politicians, talking about the aim of the project, itself. And yeah, it started out a bit slower, but once it got rolling, then it was rolling. So, I think the moderation was very important in the sense that it’s there to help guide the audience when the audience needs it. But it doesn’t necessarily make it good or bad. It makes it harder for me; it’s more work.

SJH: Yeah, you’d have to be very on your game.

DA: Yeah, but the first trials I did of it had no moderation and they absolutely sucked, they just kind of puttered out. And that’s when I realized that even if that person has no other purpose than to push a button on the karaoke machine, that person has to be visible and active in the participation of people.

SJH: “Puttering out” – what does that look like?

DA: A few people did them and then no one knew what to do after that. And the funny thing is, I went to a lot of karaoke shows and the best karaoke shows are moderated. So, it became very clear that this role has to exist.

SJH: In your work, generally speaking, how do you think about the audience when you’re creating a piece?

DA: I always try to think from the perspective that the audience is smarter than I want to believe that they are. I think that comes from a lot of personal reactions to art; there’s a lot of stuff where I’m either treated like I’m completely stupid or I look at something that you need a PhD just to look at it. I try to think somewhere in the middle. I need to be able to simplify this down in a way that’s understandable, but it still has depth.

And so, with something like White Guilt Clean Up, it’s about trying to be an ally, but it’s also a lot deeper than that. A person of color, who feels like she doesn’t have a voice and now all of a sudden she feels like someone can speak for her, and now she feels like she doesn’t have to defend herself all the time. That’s huge. I think that people have been able to figure out that it’s not a punchline, there is a complex thing that’s happening here. It’s the same thing as Politaoke – sometimes people come in and think that it’s a way to make fun of politicians and then they get really into it, and you end up with the Palestinian kid feeling like someone’s listening to him for the first time. But the packaging, itself, is not so heavy. It’s complex, but it’s simplified in a way.

SJH: If there were a spectrum of counter-culture to mainstream, where would place yourself?

DA: I think it’s somewhere kind of in the middle. It’s in the same way that I said that I’m not really interested in preaching to the choir, so I can’t be too counter-culture, but the mainstream has no interest in me, so it’s the people in the middle. That’s definitely what I’m going for; clearing it through the middle. And it’s not about dumbing it down or not addressing opinions. For me, what’s interesting about making work that’s so directly political is that you don’t actually have to tell anyone what to think; if you give them the options and let them figure it out themselves, nine times out of ten, they’re going to agree with you. But if you yell at them or you just tell someone what they should think, they’re not going to agree with you because you’re telling them to agree with you.

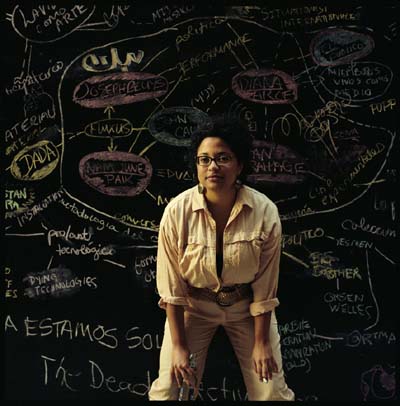

Pictured: Diana Arce

Pictured: Diana Arce

SJH: What is the change that you would most like to see happen in the world?

DA: That’s a tough one. Social, political, economic equity for all people…never gonna happen, but it would be so amazing if it could, and it would end a lot of the shit that’s happening right now. You wouldn’t have the rise of Nationalism…they almost elected a Neo-Nazi in Austria. It’s 2016; it’s like everyone forgot what happened. But I don’t know, I don’t really have a very positive outlook on legislative or social change. I don’t think that governments really care. Or, the people who do care either get burned out or they get sucked into a network of doing what the government should be doing that they’re not doing. It’s not sustainable.

SJH: So, if change is possible, it’s short-term? Putting out fires?

DA: We’re mostly putting out fires, but the change has to come from socialization. It’s the way that people are being taught to interact with other people. I don’t think it’s something that’s going to come quickly; I think it’s a generational issue. If we do enough right things now and teach these younger generations of people what’s up, get them on board early, then a generation or two from now, something can happen.

SJH: Do you see your work as a piece in that process?

DA: I hope! That’s the aim of it – I wouldn’t be doing it if I didn’t think that I could reach at least a few people. I think that’s the end game, but I don’t expect to see any immediate results. I’m okay with that. If I can get the guy who’s married to the Mexican woman to realize that it’s bad to like the Constitution party and that he should really try to have a better understanding of politicians before he pledges his support to someone who would deport his wife, then I’ve done something. And maybe he could teach his kid that and maybe they will do something with that. I think a big issue is that people just don’t understand things that are different, and there’s a lot of fear associated with that. If we can remove part of the element of fear and teach people to be a little more empathetic, then it gets harder to support things where you see that it’s actually destroying other people.

To learn more about how you can work with Politaoke, White Guilt Clean Up, or Artists Without a Cause, visit

www.visualosmosis.com

*The Center for Political Beauty created an artwork that called on the German government to change an antiquated law that prevents refugees from flying from Turkey to Germany. If the law was not overturned, they said, it would be equivalent to the German government sentencing the refugees to an almost certain death. To illustrate the stakes involved in the situation, Political Beauty set up an arena with four tigers and asked refugees to volunteer to be eaten by them. In the end, no refugees were eaten, though some did volunteer. Click here to read the Center for Artistic Activism’s full interview with André Leipold, one of the core members of Political Beauty.

You must be logged in to post a comment.