“People don’t like the things that I do. At all. The problem is that I still do them. So it’s kind of like, it would be easy to throw me out for a lot of reasons, and I have gotten bounced. But I’m still working. That’s enough.”

“It took three hundred years to get rid of slavery and segregation in this country. So do you think that means that the people in the nineteenth century who were abolitionists or who were anti-lynching activists were losers and that they failed? …. f you can’t measure the effect of individual art practices directly on social formations in this immediate sense, then do you want to consider them all failures? Or shouldn’t we start looking at the big picture.”

Coco Fusco is a New York based interdisciplinary artist and Director of Intermedia Initiatives at Parsons The New School for Design. She is an author of five books, participant in multiple biennials, and shown in museums around the world.

Lambert & Duncombe How do you know when you’re work has been a success?

Coco Fusco: I think “success” is being a mid-career artist who hasn’t disappeared even though I don’t sell works for huge amounts of money.

I haven’t been able to work on a very big scale. The reason for that is it becomes so expensive that the principal concern becomes about getting money to do things. And I don’t have a big infrastructure, I don’t even have an assistant here. I do it all, and occasionally, when I can, if I find a person who is really responsible and interested and wants to work, I will employ them on a part time basis to help me with a particular project. But I also have a full time job and am a single mom. So I have to work within my means.

But also, the way the culture industry works, you either, if you become very dependent on funding, you become very…

S & S: Dependent on funding.

CF: And dependent on their rules. And a lot of those rules don’t work. So it can get very expensive to tour if you start using a lot of technology and you need a lot of technicians and all that. So I have to think about small-scale things that can leverage my strengths, but allow me to have a relative degree of autonomy. ‘Cause I already have to interface with the university in order to survive, and I represent everything that universities would like to destroy: a woman of color who talks back. But a woman of color who’s an artist with a PhD: oh no! Then she’s not just kind of a crazy person who you can throw out the door.

People don’t like the things that I do. At all. The problem is that I still do them. So it’s kind of like, it would be easy to throw me out for a lot of reasons, and I have gotten bounced. But I’m still working.

That’s enough.

S & S: So you’re saying that just surviving as an artist – a radical, black, female, under-funded artist – has its own impact. This is it’s own form of success.

CF: Well, I don’t even think I have that huge an impact. I just think that it’s: “oh my god, she’s still around!” A lot of my peers are of the first generation of non-white artists to actually make it in the market here, to actually have impacted the art market….

S & S: How important is that?

CF: I do think that there’s something to be gained by actually forcing commercial institutions, or even major cultural institutions that are non-profits but for all intents and purposes they’re like multi-nationals (for me the Guggenheim, MoMA, they’re like multi-national corporations), I do see a value in making incursions into those spaces. Because money talks. And when your works are in those collections, you actually do change the way that art history has to be taught.

When I spoke at MoMA I probably got more play in the media for that fifteen minutes than I got for two years of touring with the piece. When I’ve done work in the Whitney Biennial it’s the work that gets out to the public because of the media machines that these institutions have.

S & S: To some extent, those institutions do open doors.

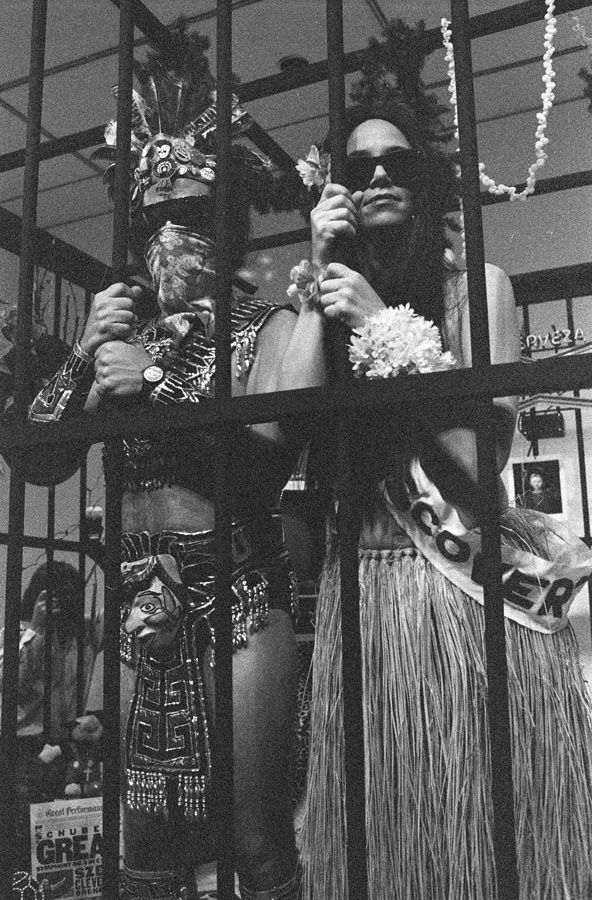

Every week I get a request for the caged Amerindian piece from somebody who’s writing about it still—and I did that piece with Guillermo in 1992. I kid you not – this is not about vanity – every week I have to answer a permission request, a query from somebody who’s writing a dissertation, writing a paper, or doing something for their book, or they need an image or they want to interview me again or they read about it in their class. I like to think that there was some value in the piece, but it’s also that it was at the Whitney Biennial of ’93. And so all these people who don’t see work that’s shown in small non-profit spaces or in festivals or whatever gets access to it at the Whitney Biennial. So I see a benefit to those kinds of “institutional collaborations,” shall we say.

S & S: But is sounds like you don’t think much about success in terms of these “institutional collaborations.” Why not?

CF: There was a lot of cultural debates around diversity and democracy in the ’80s, which is when I was in my 20s – about trying to overcome a history of exclusion, so the demand was for inclusion. Many of my peers are of that generation, and I see a value to what they’ve done, but I’ve also seen how the more ensconced you become, the more you become like the people in the institutions that support you. Once you get inclusion somehow that starts to depoliticize many people.

Not everybody, but many people become increasing depoliticized and they’re encouraged by what the market is willing to support. And let’s say for example in relation to African-American cultural production, the market is much more willing to support work that is focused on style than on the political condition of blacks in this country. The market is much more willing to support more, let’s say, abstracted, attenuated relationships to social issues. So you see people start to make more and more work about the stuff that is more easy to digest.

S & S: So you see both the art market and major art institutions having a strong influence on content. How do you avoid that happening to yourself?

CF: I don’t sell that much, so I have no incentive to–

S & S: Ahh, the benefits of the lack of “success”! But seriously, how do you avoid the mainstream institution’s interests from becoming your own?

CF: Some of it is about the kinds of things that interest me. I am not an intuitively driven artist although – now that I’m about to turn 50 and I’ve been at this for a while – I do allow a kind of internal mechanism of mine to filter the things that I look at and go “oh, should I do something about that?” And if I wake up in the morning several times in a row thinking, oh I should do this, then I’ll probably eventually find a way to do it. And that process is not entirely analytic. It is more about kind of going for the gut. What hits me in an issue that I understand intellectually to be important. What is it about – what gets me in the gut, right? It may have to do with my personal history, it may have to do with an antagonistic nature of mine. It may– I don’t know. But I tend to go more for difficult issues.

S & S: Can you give us an example?

CF: When my peers were in this big hoopla moment in the late ’90s about the information revolution and the information super highway and cyberspace is this great kind of paradise for intellectual exchange and newfound freedoms, I was going into assembly plants in Mexico and talking about the crappy work conditions for the women who were making the cell phones and the televisions. Maybe I just like to rain on people’s parade, I don’t know. But it seemed to me that, hey, there were a lot of people in the nineteenth century who went into the worker’s factory and into the ghettos and talked about how fucked up that was, so why shouldn’t I do the same? Especially if particular social or cultural groups that I have an affinity with are the ones who are the shock troops of this kind of thing.

Interestingly this piece that I made about the maquiladora workers, you know it just never stops traveling. Somebody always wants to see it somewhere. Right now it’s in Spain and in Texas and in Philadelphia. All at the same time. And I keep getting more and more requests for it. So it never sold, but it’s never stopped traveling.

S & S: So, we know this may sound like a stupid question, but why make art about these issues? There are lots of other ways, maybe more effective ways, to effect change: organize demonstrations, write policy reports, launch a petition. Why not do that?

CF: I would do all those things. When I was working on the project about maquiladora workers who disappeared and all that, I supported mothers of the disappeared in Juarez, I made petitions online for them, I went to march with them to the Organization of American States, I did those kinds of things, and I made my artwork, and I did all those different things. But I’m still an artist.

S & S: Do you see a particular political value in the art?

CF: Yeah. Well, number one, I’m not a politician or a lawyer or a lobbyist. Number two, I also think that public opinion is shaped as much by the culture industry as the discourse of politics. And that there are good reasons to use tools that are at one’s disposal that are not necessarily directly connected to the political.

I also think that to have an understanding of politics that is limited to organized electoral politics is not to understand how political formations work in the present. I think politicians understand that very well. That’s why religious organizations are so important to politicians. And why the Nazis were so interested in film and radio. Because they understand there’s a way in which culture, and particularly the culture of the image, works on people that direct political discourse doesn’t.

Whatever the problem is, it’s not only going to be solved one way. It’s going to be solved in a number of ways. And if you look at – what did ACT UP do? Well, ACT UP did lobbying and got involved in drug research, and also did performances and billboards, and a day without art inside museums. Sometimes there are issues that are well-suited to a kind of investigation in a variety of fields.

S & S: And maybe we, as artists, don’t have do all the variety of things that need to be done ourselves…

CF: There is this kind of the bizarre, romantic modernist throwback idea that art students have, and I see it in the classroom all the time, that you, as an individual, have to do something that effects millions of people. What kind of egotism does that speak about, right? The choice is not either “I as an individual change this” or do nothing about it. The choice is what can I do along with many others to keep on making it clear, publicly, that there’s opposition to things that happen in the world. And that’s a group effort, that’s an ongoing thing. You see a little bit of result and then two steps forward one step back, two steps forward…that’s how things happen.

Maybe young people are too susceptible to the biopic version of history where it’s all about the leaders. It’s about Martin Luther King or Gandhi or whoever you’re talking about; it’s only about the leader and not about everybody else; not about all the time, the long-term struggles that lead up to things. And I think that’s wrong.

In terms of the contribution of art, there are great examples that get taught in classes and that are remembered as being really effective. Martha Rosler came to talk in one of my classes and she was talking about a project that she did in 1989 at Dia, called If You Lived Here, that was about homelessness in New York at the time—and I remember that period when you couldn’t kind of walk through East Village without literally stepping over hundreds of homeless men—and the struggles in Tompkins Square Park, and I remember busloads of SWAT team cops pouring out and attacking the guys who were living there, I remember all of this vividly. She was talking about how the book has never gone out of print and how the show has been recreated in several different contexts, and that was 1989! So it’s like 21 years ago and the project is still alive. The Dia Foundation will never do anything like that again. But it has lived for a long time…. And we still have homeless people.

S & S: So if that piece was in many ways a success, and we still have people without homes living on the streets, does that mean that the work didn’t ultimately succeed?

CF: I think it’s not linear. You know? There’s work of mine that I haven’t performed in years that I still get asked about and that is still taught. So it’s not like I found an audience – the work is still finding audience. And that continues. That’s kind of how art works. It’s not just about that you do it and it’s done. Instead you do it and you put it out there and then it kind of goes and goes and goes and goes and goes. My work, for example on the caged Ameraindian was not received favorably in the beginning. It’s received much more favorably now than it was when it was first made. A lot of times I don’t get a lot of pats on the back at the beginning. It may come later. Or not at all.

S & S: You have be in it for the long haul.

CF: Don’t underestimate how hard it is, you get older, life gets more expensive and complicated. It’s really hard to keep doing stuff that is not well remunerated or that gets you into trouble when you’re not 25. And when you could lose your house, or you might not be able to pay your kid’s tuition, or you just can’t get another job because you’ve been blacklisted at different places. Those are real issues.

S & S: Thank god for 25 year olds willing to get into trouble.

CF: Yeah, I suppose. But also thank god for Martha Rosler. I mean, for somebody who’s been at it for 40 years and won’t give up, right? I think it’s very, yes, it’s very good to capitalize on the energy of 25 year olds, but there, it’s also true that you need to direct that energy very effectively in order for it to actually yield something. And also there’s energy that quickly dissipates. I’ve seen it among my own peers. People were a lot more, who were a lot more interested in making trouble when they’re young stop being interested at a certain point because they want to have easier lives. Or because they stop believing in the value of what their work can do.

S & S: This kind of brings us full circle because now we are back to the question of how we determine things like “value” or “success” when discussing political art.

CF: I find as a teacher that I have a lot of students who want to be able to quantify effect and measure effect because they have a very strange set of assumptions that they operate with about how to measure value of cultural practices that purport to bring about political change. In other words, they’re always like, “well, it didn’t actually do that in the immediate sense. And so therefore it was unsuccessful, right?” Now this may come from the prejudices that are expressed by teachers overtly and indirectly, but I think that it’s also a rather short view, a truncated view, of how things happen in the world and in history. And that frustrates young people because they haven’t lived long enough to wait for anything to change.

It took three hundred years to get rid of slavery and segregation in this country. So do you think that means that the people in the nineteenth century who were abolitionists or who were anti-lynching activists were losers and that they failed? How long did it take the non-violence, through non-violent means, to decolonize India? Decades of struggle. So does that mean that each individual instance is a failure? Or if you can’t measure the effect of individual art practices directly on social formations in this immediate sense, then do you want to consider them all failures? Or shouldn’t we start looking at the big picture?